Boas’s recognition of a plurality of cultures and his cultural relativism still persist to present day. Boas lived and worked closely with the Inuit peoples on Baffin Island, and he developed an abiding interest in the way people lived.īoas’s ideas of culture being a relatively autonomous totality with interrelated parts built on the legacy of Johann Herder an eighteenth-century supporter of the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man as well as a critic of the German nobility. The first of many ethnographic field trips, Boas gathered his notes to write his first monograph titled The Central Eskimo (1888). In 1883, Boas traveled to Baffin Island, the largest island of Canada, to conduct geographic research on the impact of the physical environment on native Inuit populations.

#Franz boas free#

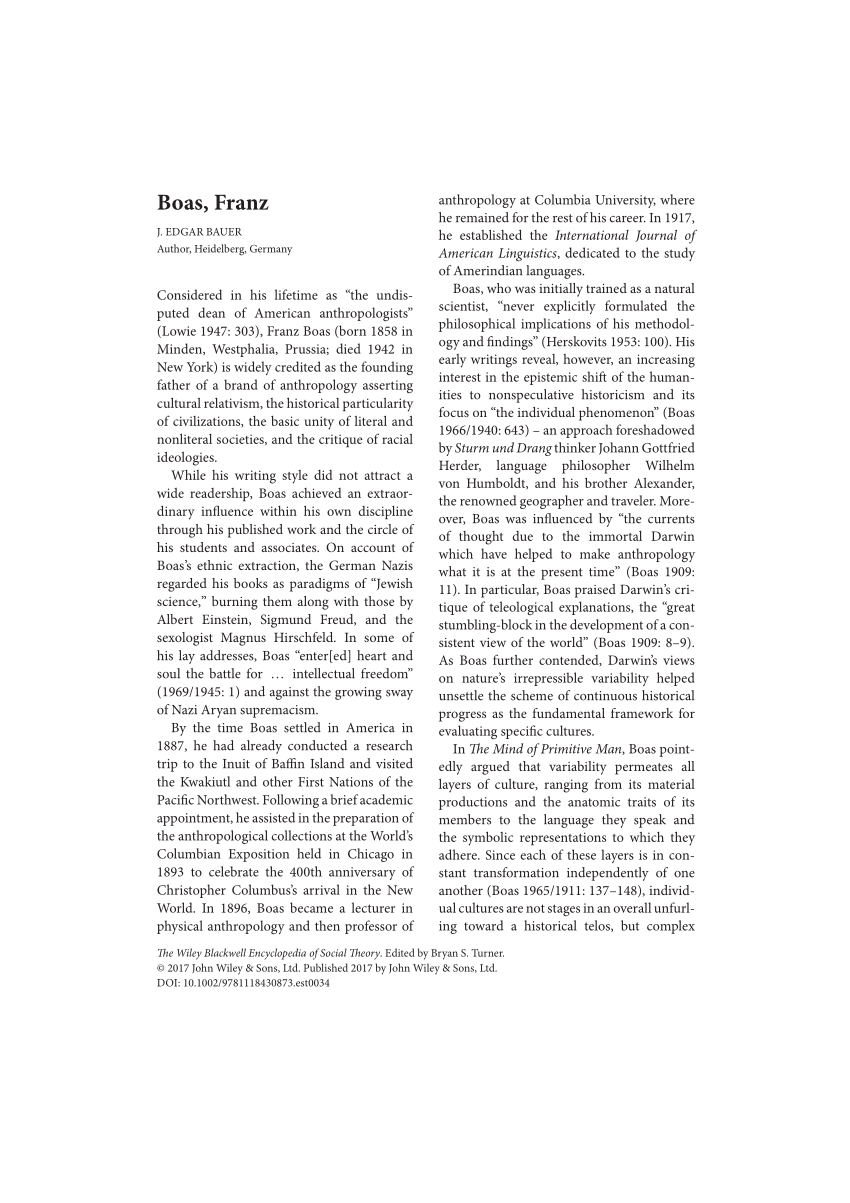

(Patterson, 2001) Boas thoroughly believed that individuals had the right to challenge “the authority of tradition” in ways that free us from the errors of the past” and that “prevent individualism from outgrowing its legitimate limits and becoming intolerable egotism.” (Boas, 1938 as quoted by Patterson, 2001) He held a lifetime commitment to freedom of thought. He is famed for applying the scientific method to the study of human cultures and societies, a field which was previously based on the formulation of grand theories around subjective knowledge. Like many such pioneers, Boas trained in other disciplines during his education, including languages, geography, psychophysics, and philosophy, and was influenced by neo-Kantian thinkers who gave expression to liberal and socialist ideals in the oppressive political climate of Bismarck’s Germany during the 1870s and 1880s. (Willis, 1975 as quoted by Patterson, 2001) Professionalism acted as a brake on Boas’s political activism, at least until his later years. These commitments were more fundamental than the professionalization of anthropology, although professionalism was sometimes strong enough to clash successfully with Boas’s politics. (Patterson, 2001) One of his biographers noted that his vision of anthropology was shaped in part by his political commitments: Being a political radical, a foreigner to America and a Jew, Boas felt a profound impact from being a part of this transformation.

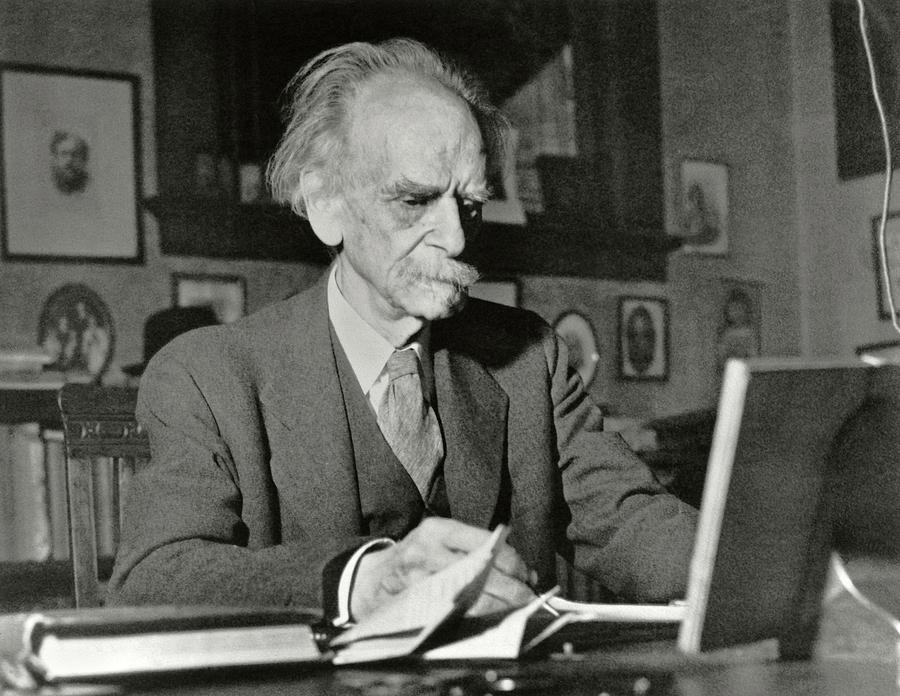

This shift, in turn, provided credentials and certification to the next generation of anthropologists, and was occurring during a period characterized by extreme discrimination against people of color, immigrants, women, and the poor. German-born Franz Boas (1858-1942), often referred to as the “Father of American Anthropology”, played an important role in professionalizing American anthropology and shifting the profession’s center from the federal government and private museum to the university. We will cover each of their backgrounds, their greatest contributions, and their overall influence on the discipline of anthropology.

Both of these influential researchers are of great importance to our examination of the history of anthropology and I will discuss both of them in this paper. Margaret Mead was one such later scholar, whose research in the Pacific Islands proved to be enlightening on the nature versus nurture debate, challenging the assumptions of the universal stages of human growth and development, and on childhood and socialization. Indeed, the 20th Century was pivotal to the development of modern cultural anthropology.įranz Boas was an instrumental American scholar in the founding of the discipline of anthropology, and paved the way for later scholars to further define the goals and range and to broaden the study of culture. Scholars such as Ruth Benedict, Eric Wolf, and Margaret Mead were among this group of anthropologists who expanded on the contributions of the fathers. (Patterson, 2001) By the mid-1900s, several key scholars emerged and further defined the scope of the discipline. These founders of the science made substantial contributions to the growth of the discipline.

Bronislaw Malinowski, who conducted fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands and taught in England, developed this method, and Franz Boas promoted it. However, by the 20th century most socio-cultural anthropologists turned to the study of ethnography, in which an anthropologist actually lives among another society and participates in the culture while conducting scientific research.

In the nineteenth-Century, ethnology, which involves the organized comparison of human societies, and relied on second hand materials collected by missionaries, explorers, or colonial officials, earned the ethnologists their current label of “arm-chair anthropologists” developed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)